It’s time for this series to make its first foray into Africa: I’m going to start in Nigeria with “Agege bread”, named after the suburb of Lagos from which it came. It’s a bread with a story and I’ll retell the basics, with the help of this great video by “For Africans By Africans”.

Bread wasn’t native to Nigeria until the later part of the 19th century, when it started to be brought in by immigrants from the Caribbean. In 1913, Jamaican-born Amos Shackleford arrived in Lagos and set up a bakery business which thrived to the point where he was considered “the bread king of Nigeria”: his “Shackleford bread” would arrive in Agege by bus until services were disrupted in the wake of independence in 1960. A local by the name of Alhaji Ayokunnu set up his own bakery and gave his product the name “Agege bread”. Subsequently, an enterprising community leader negotiated with the suburban railway for trains to stop in Agege, which became the means by which Ayokunnu’s bread colonised the city and won a place in Nigerian hearts.

It’s a slightly sweet white loaf, usually oblong and baked in a tin, whose defining characteristic is that it’s fabulously soft and fluffy. It also keeps well, which is not an insignificant feature in Lagos’s warm, humid climate. A big part of this comes from the kneading process which uses a machine called a “dough brake”, introduced by Shackleford, which looks rather like a washing mangle or a giant pasta machine: the dough is repeatedly squeezed between a pair of rollers.

A bad episode happened in the 1980s, when President Babangida banned imported wheat. At the time, home grown Nigerian wheat was of lower quality, so bakers started using “improvers” to artificially boost the softness and fluffiness of their product. At least one of these, potassium bromate, has since been found to be carcinogenic and has been banned; other alternatives remain.

I don’t want to use improvers, but I do want to get to something like the approved fluffiness, so I’m going to follow the lead of Nigerian cook Nky-Lily Lete and use the Scandinavian “scalded flour” method – if you want to see why this works, take a look at this post on Bread Maiden, which also describes a newer method invented in Taiwan called Tangzhong.

Since I don’t have access to a dough brake, I’ve simulated the effect by repeatedly rolling the dough with a rolling pin and reforming it. To speed things up, I’ve done some kneading in advance with the dough hook of my stand mixer: if you don’t have one, you’ll need to spend longer on the kneading process.

- 500g strong white flour, plus more for kneading

- 200ml boiling water

- 5g yeast

- 50g sugar

- 80g warm water

- 40g milk

- 50g butter

- 35og flour

- 1tsp salt

- Mix the boiling water with the 100g of the flour. Cover the bowl and set aside to cool, for at least one hour (you can do this overnight if you want)

- In a bowl, mix the warm water, milk, sugar and yeast. Leave for 10 minutes or so until frothy.

- Soften the butter (my preferred method is to chop it into small pieces and set it aside at room temperature while you do everything else.

- In the bowl of a stand mixer, mix the remaining flour with the salt.

- Add the scalded flour and the wet mixture to the dry mixture and mix thoroughly (either with your hands or with the paddle attachment). Leave for 10 minutes.

- Add the butter, mix it in and then mix with the dough hook for around 5 minutes

- On a floured board, roll out your loaf, then fold it up, picking up as little flour as you can manage. Roll it out again and repeat until the dough is very elastic.

- Shape the dough into an oblong and put it in a baking tin. Cover and leave until well risen – depending on your kitchen temperature, this could take anything from one to four hours.

- Preheat oven to its hottest setting – mine was 250℃ non-fan.

- Bake, covered, for around 20 minutes. The bread should come out soft, risen and not dried out.

It’s best to at least try this bread when it’s fresh out of the oven, even if you’re keeping most of it for later!

Note that I haven’t bothered with a knock-back and second rise: they don’t appear to do this in the Agege factories. But there’s nothing stopping you from doing this if you want.

Slight caveat on the photos here: the quantities in this recipe turned out to be too large for my smaller bread tin and rather too small for the larger one. The resulting bread should really be square in cross-section: to achieve that with the tin you can see, I’d really need to add 50% onto all the quantities here.

The usual in-process shots:

Scalded flour

Butter being softened

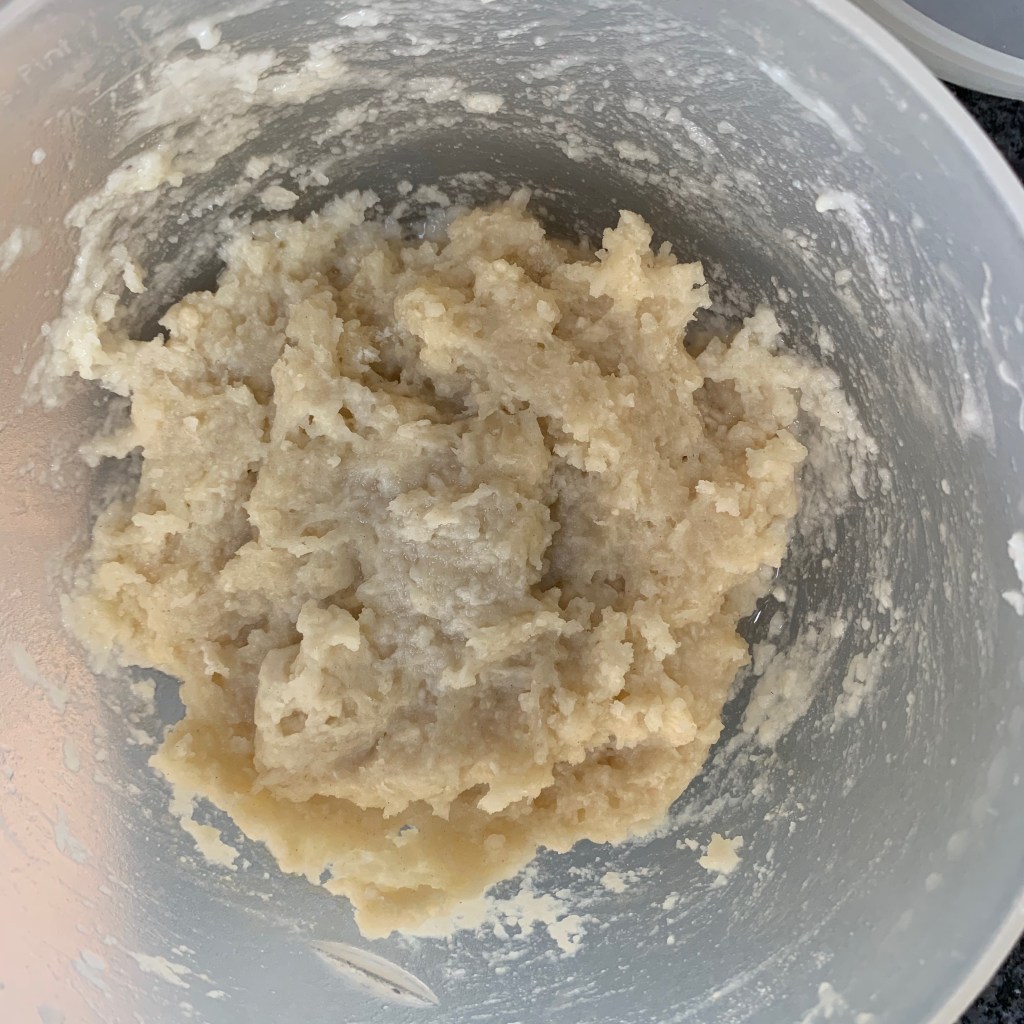

Dough before kneading

Flattening the dough

Dough after kneading

Ready to bake

One thought on “Around the world in 80 bakes, no.18: Agege bread from Nigeria”