A visit to Porto is a kaleidoscope of different aspects of Portugal: the old and the new, the vibrant and the sleepy, the glitzy with the derelict – overlaid with the cultural flavours of the country, some of them authentic, some of them artificial. We spent three nights in Porto at the start of a road trip from north to south of the country: here are some things we saw and some impressions.

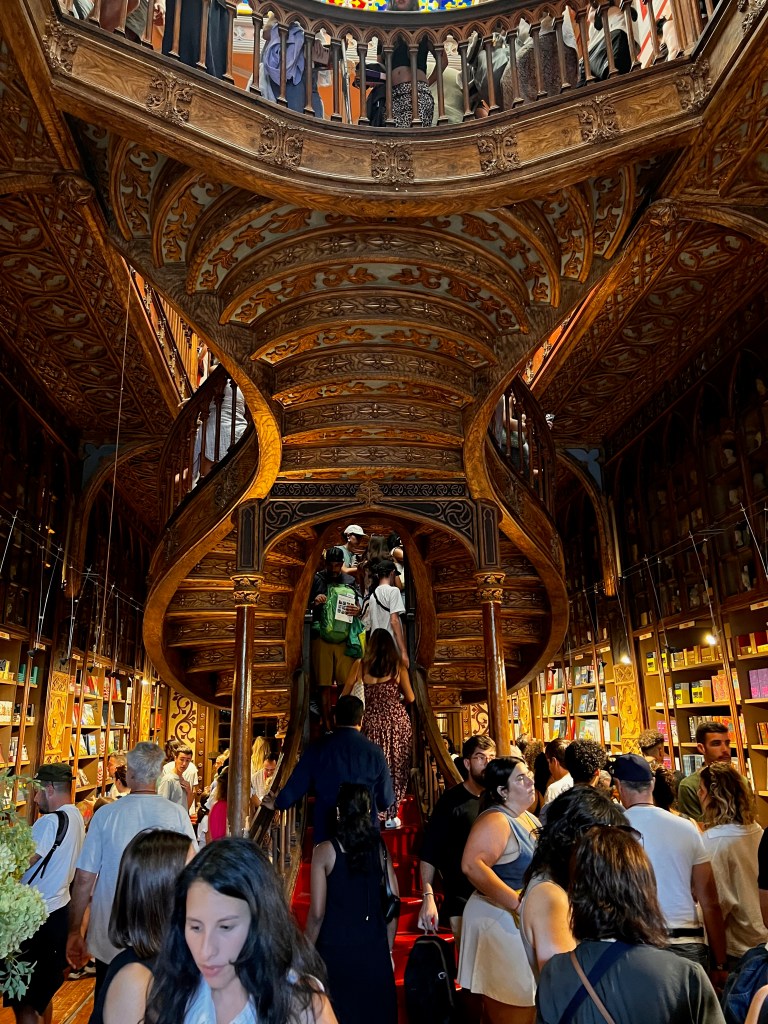

One place that sums up many different faces of the city is the Livraria Lello. Built in 1906, it boasts truly stunning Art Deco architecture with a central staircase, pretty enough to have been described as “the most beautiful bookshop in the world” by a 2006 article in El País. That strapline has been taken up enthusiastically by the owners (along with the probably apocryphal story that the shop inspired scenery in the Harry Potter books), and the Livraria Lello now attracts zillions of visitors at €8 a throw, refundable against purchases. It’s clearly a favourite with the Instagram community, so you have to book your time of entry in advance online and keep to it. Most time slots sell out, at least in summer.

The bookshop is full of treats for serious and infrequent readers alike (a large section of José Saramago for the serious, beautifully bound translations of famous works of literature into many languages for the souvenir hunters. This is the Portuguese taking their heritage and turning it into a tourist attraction – and by the way, the owners use the profits to fund other heritage activities: recent ones include restoring a theatre and acquiring a classic book publisher.

Turning right on exiting the Livraria Lello, a short walk up a steep hill gets you to the Igreja do Carmo (Carmo Church) and Carmelite Monastery, whose outside shows you another omnipresent feature of Porto (and Portugal in general): exquisite blue and white wall tiles (“azulejos” in Portuguese – although confusingly, the word is not derived from “azul”, meaning blue). The ancient tradition of tile-making is alive and well, so you’ll see tiles everywhere: on inside or outside walls of buildings of every kind, on graves, as tableware. We even saw a set of gorgeous tiles in the humble interior of a coin-op launderette.

Steep hills, you’ll soon discover, are a feature of Porto. The city is built on a steep incline leading down to the river Douro, but that’s just the start: the topography just seems crinklier than other places, and you’re continually going up and down vertiginous inclines to get from one place to the next. It makes for spectacular views across the city from all manner of places, with most of the best viewpoints occupied (of course) by the many churches.

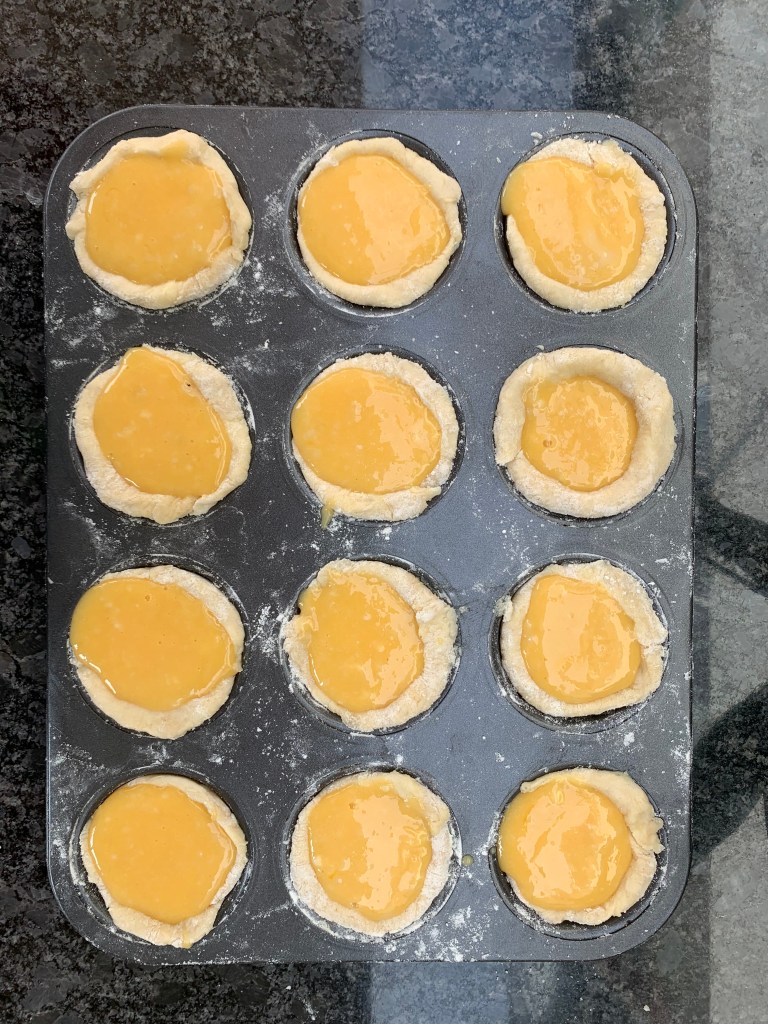

Working your way downhill from the Igreja do Carmo or the Livraria Lello and keeping the Sé (the cathedral) on your left, a maze of streets leads you down to the waterfront, known here as the Ribeira. On your way, you’ll see Porto in its full incarnation as a tourist centre, at all levels of the market. There are sleek, trendy-looking hotels, either new steel-and-glass or conversions of old buildings. Ordinary mid-priced hotels abound. You’re awash in tourist-oriented “sample the local food” eateries offering pastéis de nata (the iconic Portuguese custard tarts), pastéis de bacalhau (rissoles filled with a white sauce made with salt cod and cheese) and other Portuguese staples, not to mention port and tonic for your aperitif. We found one shop entirely dedicated to attractively decorated tins of sardines (O Mundo Fantástico da Sardinha Portuguesa, which turns out to be a nationwide chain which even has an overseas branch in New York).

It wouldn’t be overly harsh to label a great number of the shops and eateries as standard tourist tat, with the concentration of those increasing as you approach the waterfront. But that would be to ignore the many places that are far more worthwhile. We ate fabulously inventive, modern cooking in a restaurant called Emcanto, recently opened by a couple of Brazilian chefs, that we came upon by accident (it didn’t seem to feature highly on the standard lists of TripAdvisor and friends). We saw it in a pretty cul-de-sac and were intending just to stop for a drink, but the welcome was so warm that we ended up staying for the food and were thrilled that we’d done so. As well as the traditional cafés, there’s an increasing number of the hipster variety: Nicolau was an excellent brunch place (we were lucky to get in, given that the place was packed to the gills shortly afterwards). But the place that epitomised the new Portugal for us – the one that’s attracting young people from all over the world to set up businesses – was Honest Greens, a chain with branches across Spain and Portugal. Its three founders were frequent independent travellers from France, Denmark and the US who were fed up with not being able to get healthy food; they’ve created the best places for a lunchtime salad that I know, with everything fresh, delicious and efficiently made to order (and at decent prices).

If, by the way, you go around the other side of the Sé (another steep climb, but you’re getting the idea by now), you can get phenomenal views of the city as you reach the spectacular Dom Luis I bridge towards Vila Nova de Gaia on the other side of the Douro, engineered by Théophile Seyrig, a disciple of Gustave Eiffel.

For fish and seafood, our hotel advised us to head in the opposite direction to the seaside suburb of Matosinhos, where there is a cluster of seafood places (the Portuguese name is “marisqueria”). It was about half an hour each way by car (the metro goes there but takes longer) and it was well worth the trip, with super-fresh fish cooked by people who evidently knew their trade. We were looking for simplicity and freshness rather than complex, fancy cooking, and that’s exactly what we got. By the way, the hotel warned us off any of the city’s options for tasting port, which it considered as all being tourist traps, recommending that we take a trip up the Douro river to the wine-growing region. It’s around 80 minutes each way and, sadly, we ran out of time to do it. Next time, hopefully, because it’s not just port that comes from the Douro region: we had some memorable red wines from there.

Our small hotel, the Jardins do Porto, was slightly north of the centre of Porto in an area whose economic state was decidedly mixed – at least as demonstrated by the state of repair of the buildings. The hotel itself had been beautifully done up and was being kept in immaculate condition. But that made it an exception compared to most buildings in the nearby streets, of which many needed a serious lick of paint at the very least and some looked quite dilapidated. We were told about two specific problems: firstly, too many landlords have tenants at very low controlled rents and hope to flush them out by leaving the properties to rot, and secondly, that the base value for property taxes gets updated only infrequently, so for many buildings, property taxes are so low that leaving a building empty is a viable option for the owner. One suspects that serious reform of the property tax regime is needed (as, to be fair, is the case in many European cities, not least my home city of London).

Away from the city centre, plenty of Porto is very modern. Just a couple of streets away from our hotel, the Trinidade shopping centre is suitably glitzy. A few streets away, in the main shopping area round the Rua de Santa Catarina, the Mercado do Bolhão (the historic market) has been done up beautifully. Half a kilometre west of the Igreja do Carmo, passing by a pleasant museum with more blue-and-white tiles, the Museu Soares dos Reis, the Super Bock Arena hosts all manner of music concerts, as well as (for a small fee) giving you the opportunity to take in a panorama of the city from the top of its dome. Next door to it is a pleasant small park, the Jardins do Palácio de Cristal, whose wandering cockerels and peacocks are a particular delight to small children. Walk north from there and you’ll pass a lot of modern apartment blocks and offices on the way to the city’s other big concert venue, the Casa da Música.

I’ve been in Lisbon and its surroundings relatively often, but this is the first time I’ve been to Portugal’s second city. It’s been a fascinating few days.