Our recent trip to Indonesia was mainly about diving (see the previous post). But as on all diving trips, there was also a day or two of seeing around, in fairly out of the way parts of the country. Our first day out was in the small port of Labuha (population 10,000, according to our guide), on Pulau Bacan in the Maluku Islands, aka the Moluccas, the famed Spice Islands which were of such great interest to European colonists. (“Pulau”, by the way, means “Island”, and the “c” in “Bacan” is pronounced “ch”). Our second was in the considerably larger city of Manado (population 458,582, according to Wikipedia, or 1.4m for its metropolitan area) at the Northern end of Sulawesi – the large island immediately recognisable on a map because of its spidery arms.

Here, in no particular order, are some impressions that we gathered about the country.

Firstly, there’s been a lot of development, most probably in relatively recent years. My memories of past visits to Malaysia or Indonesia are of a lot of simple wooden buildings in a fairly standard style that you would see anywhere in Asia, and not all that well maintained – the climate doesn’t really lend itself to the spick and span look to which Europeans aspire, and in any case, doesn’t need it in terms of perfect insulation. In both locations on this trip, there were plenty enough of these, but there were also large numbers of modern structures in concrete and steel. The bigger and fancier ones were either government buildings or places of worship (mosques in Labuha, churches in Manado), showing clear evidence of investment from sources outside the region. But even ordinary homes included some buildings that looked very solid and well made.

The growth very much follows a ribbon development model. On both routes from our boat mooring point to the city, there was hardly any open countryside bordering immediately onto the road – for almost the whole length of the road, there was a strip of buildings one deep (be they houses, shops or something larger). These were not major roads; the road quality seemed to be very good along most of the length, but with multiple places where the weather had wrecked a chunk of road. Particularly near Manado, there were a fair number of crews mending the worst damage – but for the most part, these were very small crews with very little equiment – a couple of men with shovels and a sack of cement.

Fundamentally, Indonesia has the potential to be a wealthy country. It was a major oil producer in the past and remains a major gas producer, with an annual production of around 60 billion cubic metres – which makes it the largest in the region after China and Australia. And it’s incredibly fertile: pretty much anything can grow here. I can’t really speak for the large populous cities in Java and Sumatra, but in Manado, our guide related how a US visitor had told him that whatever apocalypse happened in the world, “you’ll be fine here. You’ll always be able to feed yourselves”.

And, indeed, the country was an incredibly foody place. We were expecting the glorious spice traders in Labuha – after all, the place has been the epicentre of nutmeg, mace and cloves for centuries. What we weren’t expecting was the incredible food market, with dozens of stalls selling all manner of fruit and vegetables, bean curds, spices, palm tree products, raw and smoked fish, chickens. The quality and vareity of vegetables was the real eye opener: ranging from characteristically Asian items like long beans and pak choi through to recent imports like avocados, through to things we’d never heard of like papaya flowers (tasty, and allegedly good for diabetics). The two lunches we had on these trips were in pretty ordinary hole-in-the-wall type places, and the food on both was outstanding, doing full justice to these lovely ingredients.

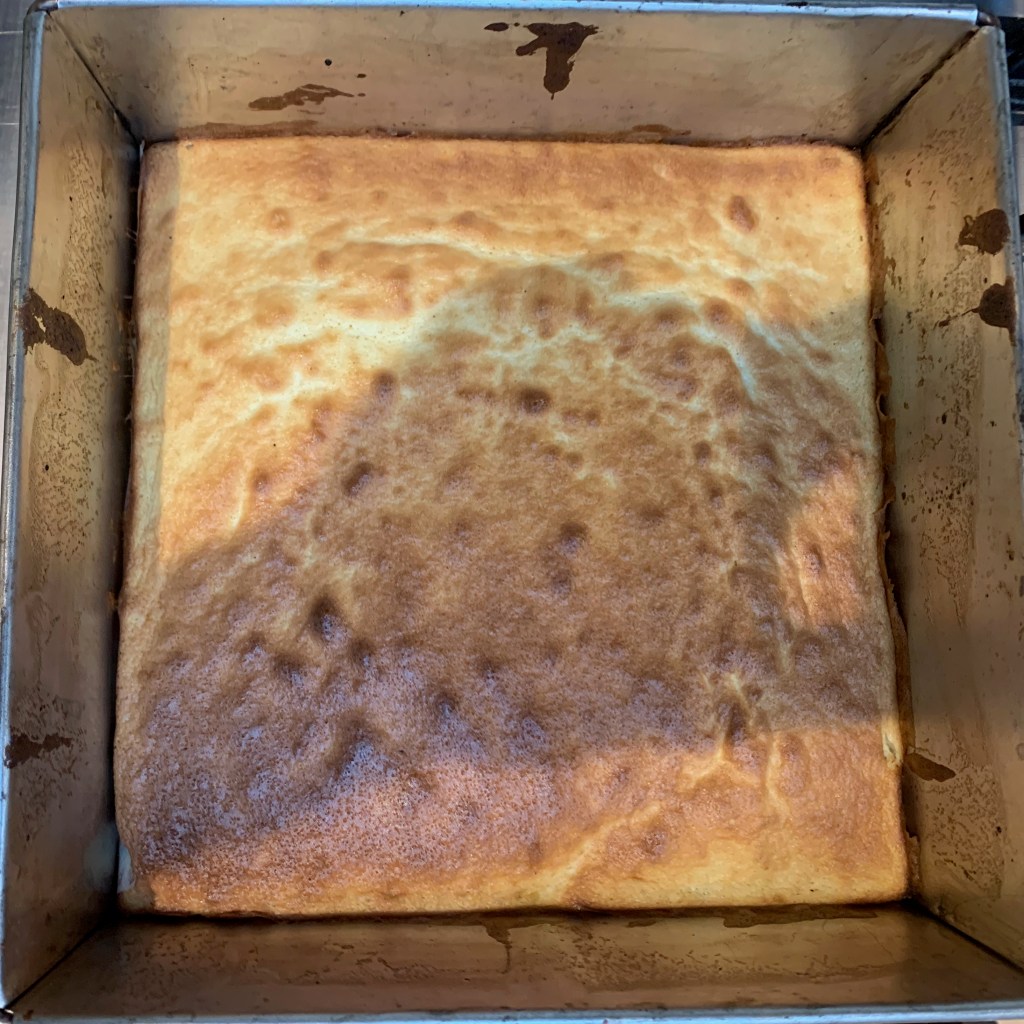

The other food and beverage surprise was a reminder that this is a coffee-growing country: one of the best cappuccinos I’ve had in a long time was served to us in the improbable venue of the Hapa Kitchen and Bakery, a small café airside in Manado Airport.

We had several reminders of how religiously and ethnically diverse the country is. While most of it is Muslim, there are big Hindu areas (most notably Bali) and big Christian areas (of which Manado is one). In the past, different religions seem to have co-existed in relative harmony, but there was a bad conflict, “the Ambon Riots”, in the Maluku Islands at the turn of the millennium. The obvious visible effect of this was at the end of class time at a very large boarding school, with hundreds of girls spilling out of the school wearing hijabs. According to our guide, the wearing of hijabs started in the wake of the Ambon Riots. The other sign of diversity was seeing instructions in more than one language: while the vast majority of Indonesians speak the lingua franca Bahasa Indonesia, it’s the primary language of only 20% of the population, with over 800 languages recorded in 2010. (Having said which, both Manado and Labuha have a higher-than-average proportion of Bahasa-speakers).

The flora and fauna are also diverse. Like most British, I suspect, I was unaware of the name of the Victorian naturalist Alfred Russel Wallace, a contemporary of Darwin who gave his name to the “Wallace Line” which splits Indonesia down the middle, with mainly Asian species on one side and Australisian species on the other. That made it surprising to discover that Wallace is very much remembered in the Maluku Islands, where he did a substantial amount of field work. Our guide on Bacan island wore a T shirt emblazoned with the gorgeous butterfly Ornithoptera croesus, otherwise known as Wallace’s Golden Birdwing. There are also many species whose latin names have the suffix “wallacei”.

Having said all this good stuff, you can’t deny that Indonesia is still a developing country, and there are things that you’d hope they will improve – for example, our seat belts only worked on one car journey out of six. Generally, attitudes to safety seem on the lax side – we certainly saw that on our boats, with luggage piled up in front of the compartment with the life jackets, or with the boat handler cheerfully smoking a cigarette three feet away from a fuel tank whose cap had been replaced by a bit of rag. And I’ve already mentioned the most important of my worries in the diving post – plastic pollution. There are separated recycling bins in Manado airport, which I suppose is a start, but we did see an awful lot of food packaging littered on the streets.

Still, those are relatively modest cavils. The truth is, all we got was a little sampler of this fascinating country. I hope I’ll be back for more some day – and to other islands.