It’s been a constant feature of my travelling life that whenever I visit a small country for the first time, the kind of country that I and most of my friends know very little about, I always find far more of interest than I could possibly have imagined beforehand. And so it has proved in my first visit to Skopje, capital of the Republic of North Macedonia.

Skopje has the unusual geometry of being long and thin – over 30 km long but mostly less than 5 km wide. That’s because it’s built along the length of the Vardar river, snaking gently from East to West along the river’s course and surrounded by mountains. The imposing Skopje Fortress is situated atop a substantial bluff immediately north of the Goce Delčev Bridge, the main river crossing point for car traffic. The Kale (the Macedonian word for fortress) has been there, in various forms and various levels of repair, since the sixth century CE, which makes it one of the oldest castles in Europe.

From the city’s river valley position, mountains are visible from most sides (which makes orientation straightforward). Kossovo and its capital Pristina are behind the Skopska Crna to the north. Closer and to the west the, Šar Mountains separate Macedonia from Albania. In the south, within the official city limits, is Mount Vodno, whose summit, named Krstovar peak, has been dominated since 2002 by the enormous Millennium Cross, a landmark that’s unmissable from just about anywhere in the city. Below the summit is a most extraordinary place to visit: the Byzantine Church of Saint Panteleimon, founded in 1164.

The church building, which has been lovingly restored, is of great elegance and beauty, with graceful symmetric proportions, domed towers and a combination of brick, stone and rendering, glowing pink in the autumn sunshine when we visited. Inside is an even more exciting sight: the many original frescoes which have been cleaned up to shine brightly even in the subdued light. The Pietà is an eye-opener with its clear depiction of Christ and the Virgin Mary as flesh-and-blood human beings, making a nonsense of the western Art History idea that Giotto was the first artist to do so – it would be 150 years before the world would see the Italian master’s frescoes in the Scrovegni Chapel in Padua.

We were shown around by the man in charge of the church and of the monastery of which it forms part, who calls himself simply Father Panteleimon. He is a phenomenon in himself: a deeply devout man, but one who has clearly had a life before taking holy orders. He spared no effort in probing us to find points of connection with his world and his experience: in our case, this turned out to be an improbable combination of beekeeping, mountain herbs, the music of Arvo Pärt and a church in Kent with windows by Marc Chagall (we were less enthusiastic about his love of Depeche Mode, whose lead singer Dave Gahan, it turns out, is also an Orthodox Christian).

While Skopje is a very old city, it is also – in a sense – a brand new one: that’s because a massive earthquake in 1963 flattened the place almost completely. The ensuing international appeal enabled the city to be completely rebuilt, which was done in a consistently modernist style. This was not necessarily to everyone’s taste, and in 2014, a massive project was launched to rebuild or re-facade buildings into a neo-classical style, with much white plasterwork and many classical-looking columns. It’s been divisive, to say the least: cheap frippery to the modernists, welcome relief to the traditionalists. Since I didn’t see what it looked like before 2014 and since I’m not as commited to modernism as the architect friend who showed us around the city, I won’t pass judgement except to say that I found it perfectly pleasant to walk round, with the National Theatre particularly appealing – although I have to confess that the rows of statues which lined the “Bridge of Civilizations in Macedonia” and the “Art Bridge” next to it were grim.

There’s a lot of street sculpture in Skopje, much of which I really enjoyed. I loved some of the statues outside the National Theatre, as well as a pair of women diving into the Vardar just by the Stone Bridge and a group of figures on its south bank near the Holiday Inn. The two pairs of lions which guard the Goce Delčev Bridge – one pair classically figurative, the other more abstracted – are controversial, not because of their quality, which is rather good, but because the lion is the symbol of the ruling party at the time they were erected, so this was a blatant piece of grandstanding.

And you can’t miss the two truly blatant examples of grandstanding that are the giant statues of Alexander the Great, on horseback in Macedonia Square, and his father Philip, on foot across the river. The pair were clearly intended as a two-fingered salute to the Greeks in the long-running dispute over Macedonia’s name: the problem is that both nations are desperate to claim Alexander the Great as being their own. The Macedonian claim is territorially correct, given that Alexander’s birthplace is inside the country’s borders; the Greek one is culturally valid in that he was clearly a product of the Hellene civilisation and clearly predated the Slavic and Ottoman civilisations that form the Macedonian people today. The dispute was eventually settled in 2018 by the solution (which I personally find rather childish) of changing the country’s name from “Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia” to “Republic of North Macedonia”). The statues, I’m sorry to say, are completely tasteless, although the nearby Fountain of the Mothers of Macedonia, which incarnates Philip’s mother Olympia as four stages of motherhood, is an altogether better effort.

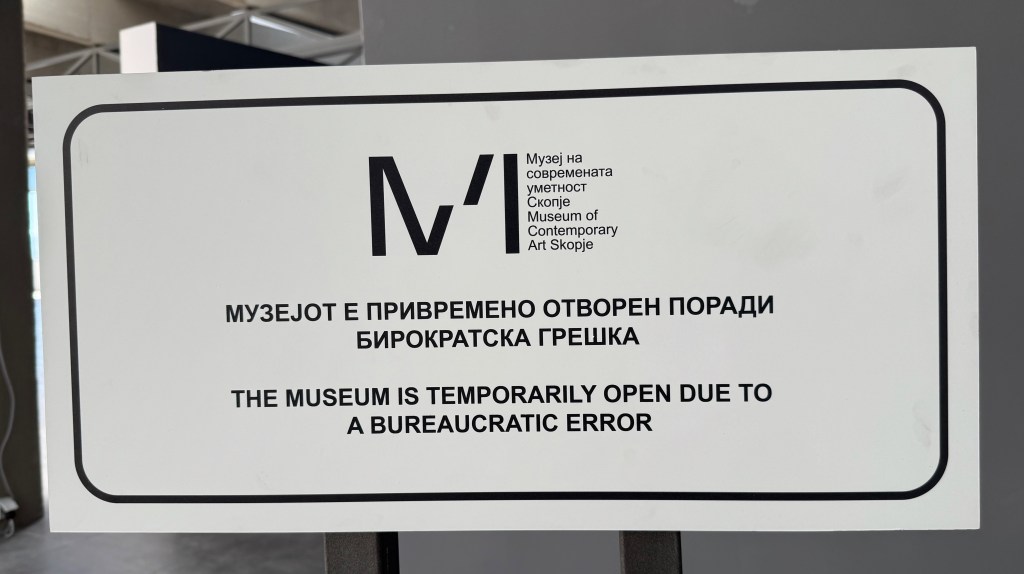

We just had time for two of the city’s many museums. The airy Museum of Contemporary Art, on the same bluff as Skopje Fortress, holds regularly changing temporary exhibitions and boasts panoramic views of the city from the terrace outside. Slightly spookily, they were preparing to host a conference of 250 FBI operatives when we arrived: I’m not sure what the Feds would have made of “Museum open until further notice”, a collection of hilariously sarcastic anti-establishment memes by artist Cem A (with delicious irony, as I write this, the museum is actually closed to host a different conference). The second was the Archaeological Museum of Republic of North Macedonia, packed with artifacts through the ages, such as the superb funerary gold mask and glove pictured here, from the Trebenishte necropolis near Ohrid in the south of the country, probably from the 6th-5th century BCE. Lake Ohrid, we are told, is seriously worth visiting, but we didn’t have time for the two-and-a-half-hour drive each way.

In addition to all this public stuff, Skopje’s broad riverbank walks, extensive City Park (surprisingly green in September after a long, dry summer) and its lively old bazaar make it a pleasant place to visit. However, the city and the country have a dark secret: corruption. Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index for 2024 ranks Macedonia as 88th out of the 180 countries it studies, and locals point to cronyism and siphoning of funds from government projects. The results are visible on the streets of the city: perfectly decent buildings are undermined by poor maintenance, while green spaces are marred by insufficiently frequent rubbish collection. What we didn’t experience (being there in September) was the winter pollution: apparently, too many people burn coal or wood, and the ensuing smog lingers because the spaces for wind to blow it away, as envisaged by the post-earthquake town planners, were filled in by buildings. Effects of corruption are also visible in net migration statistics, with far too many young Macedonians leaving the country to seek better opportunities elsewhere.

Which is sad, really. Skopje is an attractive city in a fertile country. The climate is broadly lovely. The food is great, within a fairly typical Balkan range of dishes, in which the stars are Macedonian tomatoes, which rival the best in Italy for utter deliciousness. Some of the local wines were really quite impressive. The vast majority of people we met were utterly charming. The ethnic tensions between Macedonians, Albanians, Turks and others, seem broadly contained, at least by comparison with the norm in this part of the world. Let’s hope that the gap between Macedonia’s potential and its current reality will be narrowed in years to come.